The Change Management Life Cycle; Involve Your People to Ensure Success

Every organization is affected by change. Still, organizational change initiatives fail at an alarming rate. This is because most initiatives fail to consider how changes affect the people in an organization.

To successfully implement change initiatives, organizational leaders must identify the need for change and communicate it throughout the organization. They must also engage people at all levels of the organization by involving them in the design of the implementation strategy. Lastly, leaders must actively involve the people most affected by the change in its implementation. This will help ensure employees at all levels of the organization embrace the proposed changes.

This article introduces a three-phase Organizational Change Management Life Cycle methodology (Identify, Engage, Implement) designed to help organizations successfully manage a change initiative. For each phase of the life cycle, the article describes valuable techniques for involving the people within an organization. It also discusses the importance of developing a flexible, incremental implementation plan.

Introduction

The statistics are undeniable-most organizations fail at change management. According to the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania Executive Education Program on Leading Organizational Change, “researchers estimate that only about 20 to 50 percent of major corporate reengineering projects at Fortune 1000 companies have been successful. Mergers and acquisitions fail between 40 to 80 percent of the time.” Further, they estimate that “10 to 30 percent of companies successfully implement their strategic plans.” (Leading Organizational Change Course Page).

Why do organizations have such a poor track record of managing change? According to the Wharton School, the primary reason is “people issues” (Leading Organizational Change Course Page).

The consulting firm PriceWaterhouseCoopers supports that finding. In a study entitled How to Build an Agile Foundation for Change, PriceWaterhouseCoopers’ authors noted, “research shows that nearly 75 percent of all organizational change programs fail, not because leadership didn’t adequately address infrastructure, process, or IT issues, but because they didn’t create the necessary groundswell of support among employees”

Without understanding the dynamics of the human transition in organizational change, change initiatives have a slim chance of success. If organizations, whether private or public, cannot change and adapt, they will not thrive or worse, they may not survive in today’s dynamic environment.

This article looks at the critical role that people play in the three phases of the

Organizational Change Management Life Cycle-Identify, Engage, Implement-and offers guidance on how organizations can minimize “people issues” during change initiatives.

Why Change?

Today’s business environment requires continuous improvement of business processes that affect productivity and profitability. This, in turn, requires organizations be open to and ready for change. Some of the common drivers of change include:

- Adjusting to shifting economic conditions

- Adjusting to the changing landscape of the marketplace

- Complying with governmental regulations and guidelines

- Meeting clients needs

- Taking advantage of new technology

- Addressing employee suggestions for improvements

Organizational changes happen regardless of economic pendulum swings. In an economic upswing, for example, organizations examine different ways to extend their capabilities to maximize previously untapped revenue streams and look for new opportunities for greater profitability. Conversely, an economic downturn or recession creates the need for more streamlined business processes within an organization, and a right-sized staff to implement those processes.

The Elements of Change

In every organization, regardless of industry or size, there are three organizational elements that both drive change and are affected by change:

- Processes

- Technology

- People

Technology supports the processes designed to respond to changes in market conditions. Ultimately, however, it is the people who must leverage these processes and technology for the benefit of the organization.

Let’s look briefly at how each of these elements is affected by organizational change.

Process

Business processes are defined by process maps, polices and procedures, and business rules that describe how work gets done. These processes are redesigned or realigned as new prospective customers or better ways to provide service to existing customers (both internal and external to the organization) are identified. This drives the adoption of new technology.

Technology

Technology ensures greater organizational efficiency in implementing the changes. It is a means to process data with greater accuracy, dependability and speed. Therefore, essential to any change process is a plan for introducing and systematizing the technology required to execute the intended changes.

People

Generally, organizations excel at designing new or improving existing processes. They also do well at identifying or developing technology to realize the power of new processes. However, most organizations fail to focus sufficient attention on the role people play in the processes and technology used to accomplish the desired organizational change.

As noted in the introduction to this paper, the overwhelming percentage of organizational change efforts fail because people are not sufficiently considered at the outset of the initiative. It is the people within an organization, after all, who are responsible for developing and implementing new processes, which will in turn require new technology. It is also the people who must specify, recommend, purchase and use the new technology.

At the most basic level, people must acknowledge and buy into the need for change. An organization cannot even begin to introduce change unless its people understand and support the reasons driving the change. This acceptance of change is known as the first step in human transition.

The Change Management Life Cycle

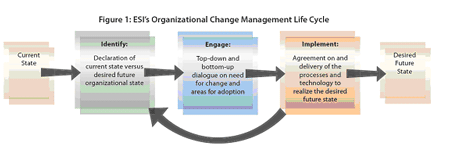

Change management is a cyclic process, as an organization will always encounter the need for change. There are three phases in the Organizational Change Management Life Cycle (Figure 1): Identify, Engage and Implement.

The elements of change (processes, technology and people) and the phases of the Organizational Change Management Life Cycle are closely linked, and their intersection points must be carefully considered. By paying close attention to how people are engaged in each phase, an organization can manage that change to adapt to any business or economic condition.

Phase 1: Identify the Change

In the Identify stage, someone within an organization-typically a senior executive spearheads an initiative to change a current process. A single voice at a very high level is often the first step in establishing the need for change. This need is then presented to the organization with a general description of the current state of affairs, offset by a high-level vision of the desired future state.

While it seems obvious, identifying the change is an absolutely fundamental first step in successful change adoption. It is important that the changed condition be described in a common, consistent language. However, organizations often fail to identify and communicate the need for change in a way that is understood and embraced by people working at all levels of an organization-from the executive suite to the individual workstation. Many leaders do not adequately consider how a proposed change (or even the rumor of one) may be received-at an intellectual, emotional and neurological level-by the people it will impact the most.

| The Neurological Roots of Resistance to Change

The prevailing contemporary research confirms that, while change is personal and emotional, it is neurological as well. Here’s what researchers now know about the physiological/neurological response that occurs when an individual encounters change:

(Schwartz and Rock, 71-80) |

If the disturbance that is produced by a change isn’t adequately addressed through some alignment intervention, this resistance to change is prolonged and can be damaging to the change initiative.

To ensure successful change, organizations should introduce a change effort during the

Identify stage using the following techniques:

Get Their Attention: Since change is disturbing and distracting to human beings, it’s important to get their attention about the change. Getting people out of their daily routines-at an off-site location, if possible-helps them create a shared sense of urgency for change and concentrate on the change message, thereby internalizing it more deeply.

Align Their Disturbances: Neurologically speaking a disturbance is a conflict between a person’s current mental model (the way they think about something) and the mental map needed to operate in a changed state. To align disturbances means to create a common disturbance among the minds of the people in the organization-to create agreement between the gap that people have between their individual current mental model and the mental model needed to operate in a changed state. When these gaps aren’t in alignment, everybody will respond to the change differently, and won’t be able to agree on the direction and intent of the organizational response needed. An important technique for aligning the potentially broad spectrum of disturbances is for leaders to craft and continually communicate a compelling vision of what the future will look like when the change is implemented.

The best way for leaders to make a compelling case for change is to consider the need for change at every level in the organization, not just at the top tier. The top-level need for change is almost always driven by bottom-line goals, and does not touch the day-to-day work experience of the organization’s staff.

For instance, a financially oriented statement, such as “our organization must realize a

20 percent reduction in operating expenses” will likely be met with fear, uncertainty and skepticism in some levels of the organization, and with ambivalence and apathy in other levels. Ultimately, it is imperative to align these varying disturbances with a clarifying vision.

Some additional people-related items to consider when identifying change opportunities include:

- Possible frustrations in performing (new) work

- Clear job definitions

- Job definitions and metrics that match the process

- Understanding of the end-to-end process

- Cultural dynamics within the organization that may inhibit people from moving to a new, changed state

- Life Cycle

Phase 2: Engage the People

Once the need for change has been identified and communicated, the next critical step is to engage people in planning for the organization’s response to the change. Successive levels of the organization must be included in a dialogue to help design an implementation plan. People within an organization must be allowed an opportunity for intellectual, emotional and psychological reaction to the desired change. Providing this opportunity enables people to become accustomed to the idea of change and to align their thinking in ways that will help both identify potential problem areas and contribute substantively to process improvement.

Consider this example: In a recent process change effort, an external consultant developed a new process, down to a very detailed level (with little input from the organization, and many requirements from executives), and proudly handed over the process design and documentation to the team responsible for implementing the new process.

The results were not surprising. The user team passively accepted the process, then aggressively refused to implement it. The user team had neither the energy nor the enthusiasm to implement something in which it had no emotional buy-in. In fact, team members told executives in the project post-mortem that they actively sabotaged the new process because “the consultants developed the process, even though we are the experts.”

| Insights-The Antidote to Resistance to Change

An important contribution of modern neuroscience to helping us be more effective as leaders concerns the phenomenon of insights-sometimes called an epiphany or an “ah ha” moment. Here’s how insights help overcome resistance to change:

(Rock, 105-107) |

General George Patton of the U.S. Army is quoted as saying, “Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.” Wise leaders know that successful change adoption depends on engaging the hearts and minds, as well as the bodies, of the people facing a changed condition. Organizational leaders need to engage the energy and enthusiasm that comes from people having their own insights, for this is where true commitment to change comes from, and where the ownership of results are truly developed (Koch).

One technique to encourage people’s adoption of a change is to conduct organization-wide response/adoption alignment workshops. When practiced effectively, these sessions allow people to contribute their own ideas about how a deliverable should be used within the organization. Once these contributions are aligned-through multi-party conversations (where much thrashing may occur!)-an aligned approach for managing and adapting to the change will emerge.

When reactions have been aligned and individuals within an organization are asked to be involved in responding to change, typical human behavior moves to addressing the problem-creating a desired direction to facilitate change.

The implementation strategy for responding to the change is then developed at a high level. The people who will be executing the strategy, as well as the people who will be impacted by the strategy, should be included in the strategy development. This high-level strategy is important for aligning and clarifying the intent of the change, as well as for establishing a direction that the change implementation will take. The strategy needs to be seen by all as a flexible plan so that the organization can adapt to changing conditions once implementation of the strategy is initiated.

Phase 3: Implement the Change

In the Implement phase, change strategies developed during the Identify and Engage phases are translated into tactics, or actions, for moving toward the desired future organizational state. Here again, people are critical of how processes and technology are created and implemented. They have direct, daily experience with these processes and technology and, consequently, they are most knowledgeable about how these components must be customized for the best results.

Most organizational change failures occur because insufficient time and attention was given to the first two phases of the life cycle: Identify and Engage. On the other hand, most organizations spend the majority of their time, effort and attention here, in the Implement phase. But, as we’ve already discussed, without the proper alignment of people’s disturbances and their response to a changed condition, successful adoption rarely occurs.

During implementation, employees throughout the organization need to remember why they are working so hard on implementing a change. Therefore, change leaders should continually remind people, using multiple media (formal e-mails, progress celebrations, informal conversations) what the change is and why it is so important.

Additionally, organizational leaders should ask themselves the following people-related questions to help ensure successful implementation:

- Does the individual have the ability or desire to work in the new environment?

- Are additional skill sets needed to transition to the new job?

- Are changes to job descriptions needed?

- Are job grades or pay impacted by this change?

- Does the change impact short-term productivity? If so, will additional support be needed to ensure business success?

If organizations successfully complete the first two phases in the change management life cycle, the implementation phase becomes essentially a monitoring activity for leaders.

They should assure that:

- Change-oriented tasks are being accomplished as planned

- Energy and enthusiasm are present

- Alignment still exists among the people

Prototyping: A Fluid Implementation Strategy

As previously noted, for change efforts to be successful, the implementation strategies must be fluid. Instead of a grand plan, sufficient flexibility in process and execution tactics must exist to respond to shifting circumstances such as market or business conditions. These mid-course corrections often take the form of rapid prototyping or alternative responses to “what-if” scenarios-considerations that are not typically included in a detailed master plan.

Prototyping monitors the thinking and activities of people-both users and implementers-as processes and technology are put into action. Its purpose during the implementation phase is to help organizations avoid getting mired in highly detailed plans that have the potential to stall change efforts.

Essentially, prototyping is another way to get people involved in the change as opposed to being recipients of the change. It gets the change underway, in small increments, rather than waiting for the master plan to be identified. Prototyping is critical to successful change management. It is virtually impossible to plan for all contingencies in the development of an overarching strategy and, yet, any successful strategy for change must be able to accommodate unforeseen challenges.

The benefits of prototyping can be seen at every level within an organization. Executives benefit from a greater likelihood of adopting change (through incremental buy-in), while staff members benefit because, as a result of prototyping, the best approach will likely be used in implementing the change. Overall, an organization’s people will have greater ownership of the change because their insights, ideas and actions are used in building the response to the change.

At the very least, an organization should adhere to the spirit-if not the letter-of prototyping to ensure that the organization is adequately equipped to handle new developments and make adjustments on the fly.

Conclusion

At the highest level, business leaders are driven by financial goals and government leaders are driven by legislative mandates. Their urgent need to meet these objectives may lead them to impose change unilaterally, rather than engaging the people to find the best way to meet a more generally understandable desired future state.

Executives who neglect the human transition required in change management will be less successful at implementing change. Successful change management boils down to improving the relationships between people in the organization in the attainment of a mutually desirable end state. An organization that is too focused on objectives runs the risk of losing sight of personal relationships.

For a change initiative to be successful, an organization must understand and address the three phases of the Change Management Life Cycle-Identify, Engage and Implement.

Organizational leaders must ask themselves these questions:

- Has the organization thoroughly identified and communicated the impending change?

- Are disturbances acknowledged and aligned?

- Has the organization engaged all of its stakeholders-at every level of the organization-in the change that will need to be adopted?

- Is the intent and direction of this change aligned throughout the organization?

- Has the organization developed a flexible plan for implementation that allows for prototyping to move continually toward the desired future state?

- Are the organizational responses aligned and institutionalized?

The human transition that is required to move from a historically acceptable way of working to one that is completely new or radically different is not to be underestimated.

Good leaders will make the reasons for change personal for everyone, not just for executives or shareholders. End-user benefits, down to the day-to-day experience of the individual worker, will create a more receptive environment for fostering new ideas-and a receptive environment is essential to creating any lasting, positive change.

If an organization can answer “yes” to each of the questions above, chances are good that its change initiative will be a success.

To download a PDF of this and other white papers by ESI International, please visit www.esi-intl.com/whitepaper

Jonathan Gilbert, PMP, Executive Director of Client Solutions for ESI International, has more than 30 years of experience as entrepreneur, educator, chief executive officer, construction manager, management consultant, project manager and engineer. He earned his B.S. in Civil Engineering from the University of Maryland at College Park, concentrating in project/construction management and environmental engineering. For more information, visit www.esi-intl.com.

References

Koch, Christopher. “Change Management-Understanding the Science of Change.” CIO 15 September 2006. 20 June 2008 http://www.cio.com/article/24975/Change_Management_Understanding_the_Science_of_Change.

Leading Organizational Change Course Page. 2008. Wharton Executive Education, University of Pennsylvania. 20 October 2008 http://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/open-enrollment/leadership-development-programs/leadingorganizational-change-program.cfm.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers. How to Build an Agile Foundation for Change. February 2008.

20 October 2008 http://www.pwc.com/us/eng/advisory/agility_foundation_for_change.pdf.

Rock, David. Quiet Leadership. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. Schwartz, Jeffrey and David Rock. “The Neuroscience of Leadership.” Strategy + Business

June 2006: 71-80.

www.esi-intl.com